Whisper Low

By Erin Hill

Somebody’s knockin’

Should I let him in?

Lord, it’s the devil,

Would you look at him…

“Somebody’s Knockin,” Terri Gibbs, 1981

December

Final grades have been submitted and the semester’s end tasks are fewer, so I sleep more deeply than I have since August. My internal machinery slows, dropping into a winter gear. Several nights before Christmas, I wake around 3:00 AM to a distinct knocking on one of my doors. I can’t tell if it’s the front door or the back, but I know I heard it. There is no one to shake awake beside me; there is no one down the hall to protect. I lie silent, breathless, and completely still. If I don’t move, maybe whoever’s at the door will go away.

March

The days are getting longer; my to-do list is lamentable. My midterm inbox is panic and favors. Yes, yes, yes, I say, it’s okay, I say, absorbing their need and their anxieties. Sleep is a fever dream, fits and starts, never more than a few hours at a time, with “remember to’s” popping up like wild spring onions, bitter and pungent. A few nights into advising week, I wake around 2:00 AM, sweaty and restless, to the sound of another knocking at the door. Did I miss an advising appointment?

June

After ten months at 100 miles an hour, slamming on the brakes is disorienting, but I’ve settled into a summer schedule. There are still committee meetings and planning and my own writing and research to do, but the pace is more humane. There is time for reading and coffee in the garden. Time for sunrise hikes and porch swings. Time for some living, ten whole weeks of it. Near the end of the month, I wake to the knocking on my door again. Now, I can meet it with curiosity. I wonder who that is? And I wonder why they persist? I wonder what they need.

September

It’s incongruous: a fresh start and a new academic year just as the wild summer growth slows. Everything dries and dies and crisps; the humidity drops and the temperatures cool and thinking feels clear and easy. We’re building relationships and momentum in class; we’re setting goals and making declarations – this year will be different. We won’t let the grind or the anxiety get to us. We’ll stay engaged. Near the end of the month, I wake from a light, easy sleep to the sound of knocking on my front door.

In some cultural folklore, a knock on the door portends death – especially if it’s three knocks in the middle of the night – so much so that this phenomenon is called a “Death Knock.” Some superstitions suggest that a single knock, on the other hand, may be more benevolent, a good spirit’s arrival, one bringing luck and fortune. Famously, Macbeth hears knocking after he kills the sitting king, thus revealing his guilty conscience, but I didn’t have any dark deeds haunting me. After so many instances of my own persistent middle-of-the-night knocking, I did what any good and curious academic thinker would do: I Googled it. Why do I hear knocking in my sleep?

Certain that a terminal brain tumor self-diagnosis was just a few clicks away, I steeled myself for the search results. My pulse quickened. I took a deep breath. I scanned the page with squinted eyes. Nothing could have prepared me for the results: “Exploding head syndrome is a condition that happens during your sleep. The most common symptom includes hearing a loud noise as you fall asleep or when you wake up. Despite its scary-sounding name, exploding head syndrome usually isn’t a serious health condition.”

I blinked.

“Whaaaaaatttt?” I said, out loud.

“This has to be an Onion article,” I thought.

I continued scanning the results page. WebMD. MedicalNewsToday. Mayo Clinic. These weren’t basement bloggers.

Was this actually a thing?

The hyperbole of the name Exploding Head Syndrome (EHS) belies its otherwise benign symptoms and prognosis. EHS is a “rare parasomnia” that involves hearing loud noises such as knocks, shots, or crashes during sleep; it can also be accompanied by flashes of light. The symptoms, while upsetting, are usually painless. The average age of onset is 58. It occurs in about 10% percent of the population, more commonly in women, though sleep researchers expect it is underreported, “stemming from the fear of being met with incredulity or misbelief.” According to one site, “Most researchers find that exploding head syndrome often occurs in people dealing with high levels of stress and physical or mental fatigue.” Treatment usually involves improving sleep hygiene and mitigating stress factors, although medication is used in rare cases.

That I was stressed was no secret to anyone, least of all me. Partners have told me to relax. When prescribing anti-anxiety meds, my psychotherapist said, “Let’s get some chill in you.” My family doesn’t understand what I, a single woman with seemingly no ‘real’ responsibilities, could possibly be stressed about. Friends issue dull platitudes like “Work hard, play hard!” in earnest, and I do not hide my eye rolls. They try to help by reminding me that I’m ‘just’ a teacher, that I’m not curing cancer. Okay, sure. But teaching and learning as liberatory practices are high stakes: education and its implications for public health, voting rights, anti-racist practices, equity work – in other words, its implications for thinking and for justice – do have the ability to cure metaphorical societal cancers, of which we have many, in late stages, and I take it seriously. Despite all this, something about my exploding head didn’t seem entirely stress related. I couldn’t explain why I thought so, especially when I blamed nearly everything on stress. Anxiety was a birthright (thanks, Mom), and I was long acquainted with its physical manifestations; in attempt to predict and control those manifestations (panic attacks, GI issues, weird skin stuff), I documented symptoms as if I were a subject in a clinical trial. According to one EHS site, “Reassurance and education on the phenomenon are often the only treatment needed.” I went in search of my own reassurance.

*****

Our family was nothing if not systematic. My mother was a surgical assistant, a secretary, a librarian; my father is an accountant. There was always a schedule – no departures or mind changes permitted. The large central calendar hung on the kitchen door, and if an event didn’t appear on that calendar, it wasn’t happening. After breakfast with the sports page, Dad began each morning with prayer and a daily review of tasks in his Bible-size Franklin Covey planner; Mom journaled throughout the day in spiral-bound $0.99 notebooks she purchased at a now-defunct local discount store called Drug Castle. On many occasions, she answered family trivia by consulting her archives: When was that ice storm when we lost power for two days? When did I lose my first tooth? What year did we drive to Michigan with Grandma for vacation? She solved more than one medical mystery by going to The Notebooks, and she prepared notes for doctors’ appointments the way I prepare notes for class.

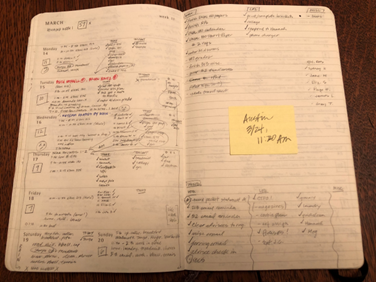

The antique bookshelf she bought me at the flea market for my birthday sits in my studio now. It anchors the room, and the old wood cracks like a living thing. On the bottom row sits a satisfying line of my own archives: 25 black, soft-cover, 8.5x5-inch Moleskine planners, one for each year I’ve been teaching. 2017’s is a little swollen (basement flood); 2016’s cover is marred (I ripped off my Ohio pennant sticker in a fit of rage when the state unsurprisingly went for Trump), but they are otherwise pristine and symmetrical. They may look chaotic, but these planners are how I (think I) keep life safe and sane and under control.

As I tracked the night-knocking, I went to the notebooks and discovered it had been going on for much longer than I realized – years, in fact. At least since 2014. My calendar notes about it appeared consistently in March, June, September, and December. Always on or around the 21st. I couldn’t square this; how could something as wildly named and seemingly unpredictable as “exploding head syndrome” be a consistent, quarterly phenomenon? But there was the documentation, in print: my knocking was seasonal and symmetrical. And then I conjured an answer: maybe this wasn’t exploding head syndrome – maybe this was my brain’s response to something happening in the natural world. EHS took on an entirely new symbolism for me, a personal acronym now of my own making. My EHS was simply a head (H) registering the arrival of the spring and fall equinox (E) on or near the 21st of March and September, and the summer and winter solstice (S) on or near the 21st of June and December. Somebody was knocking, but it wasn’t the devil and it didn’t portend evil. These seasonal transition points were announcing themselves to me. Even Mother Earth seemed to be saying, “Hey! Pay attention. We’re on a schedule here.”

*****

When Dad and I cleaned out our family home a year after Mom’s 2013 death, I stuffed a cigar box full of photos, my childhood teddy bear, and a random stack of her drugstore notebooks into a banker’s box and taped the lid shut. The box made four moves with me over nearly ten years before I ever opened it. I thought about opening it. I side-eyed it in my rental basements and garages. But random and unannounced tsunamis of grief – at the grocery store, driving, shopping for shoes, playing solitaire – told me I wasn’t ready to read those journals. She was an exceedingly private person, a woman who held everyone at arm’s length, including her own daughter. Opening those pages was an act of intimacy that both beckoned and terrified me.

In the midst of drafting this essay, I wrote “Mom’s notebooks” on my To-Do list for a solid three weeks before I made a move. On a snowy Saturday, I pulled on boots, marched out to the garage, lifted the box from a pile, and promptly placed it in the laundry room, where it sat untouched for another week. On a rainy Sunday, I peeled off the tape and opened the box. Inside: journals from 1980, 1984, 1989, 1993. I have no idea what happened to the other years or why those are the years I happened to keep; I don’t remember choosing them in particular. Sitting in my studio, heart racing and vaguely nauseated, I read without stopping for five straight hours. I was stunned at how much I remembered and how much I didn’t. Stunned at how wrong so many of my memories were. Stunned at how similar my journals are to Mom’s – hers so often a catalogue of events and meals and weather and illness and sporting event outcomes. Like mine, her pages are populated with lists, so many lists – of things to do (“sweep out garage”) and errands to run (“Penney’s for school clothes”) and items to purchase (“grey suit, turtlenecks, frames for Erin’s artwork”) and people to call (“see if some girls want to start an exercise group”). An occasional hint of emotion – “anxious,” “so tired,” “upset,” “cried today” – but rare and often only in the margins. For anyone else reading these journals, they might wonder, “Why bother? There’s nothing deep or interior or historically significant here,” but in the shorthand of our family’s systems and stoicism, I could sense the feelings under the surface of each daily ledger.

I never asked Mom what she wrote in her journal or why she wrote it. I never asked her if I could read it, and though I was a curious kid, I never snuck a peek. Here I was, at 47, sneaking that peek. I didn’t expect a big mysterious reveal in her pages or answers to existential questions, but a curious entry in Mom’s 1993 journal caught my attention: “Writing down experiences, observations, reflections, looking behind the events of the day and their hidden meaning, recording ideas as they come…” as if to remind herself what she was doing, why she was documenting her life. Our lives.

*****

I thought of my seasonal night knocking as Mother Earth; if I’m being totally honest, I liked to think the knocking was maybe even Mom herself. I know that sounds woo-woo as hell, but in the years since my mother’s death, I had lost all sense of myself, of my connection to anything of this earth, to anything spiritual. My mother loved the seasons and marked them in my childhood home with a deeply reverent, quiet beauty. She never would have called it an altar, but the vast Victorian mantel above our living room fireplace and built-in glass bookcases on either side was always adorned with something of the season. An explosion of forsythia, tulips, daffodils, and lilacs in the spring; fireworks of wildflowers in the summer; gourds and maize and ground goods in the autumn; greenery and pinecones in the winter. Mom died on Thanksgiving night but had still managed to decorate the mantel that year for fall; I sobbed when I later cleared the tokens of her artistry and couldn’t bring myself to set out the winter totems, though I know that’s what she would have wanted. Desperate for some kind of renewed connection with her, I didn’t think it so outrageous to suspect she might be behind these wake-up calls, these seasonal reminders to pay attention.

*****

Tidy, tiny reassurances for myself, and I’ve tied them up here with a pretty language bow. Worked to generate paragraphs so lyrical and raw, an attempt to make meaning of the pain. But answers? Nope. Mom’s journals, my journals, our lists, our planning – they don’t help us control much. Life is explosive. It’s a layoff, or a house fire, or a break-up – or a stage four cancer diagnosis, with fewer than eight weeks to spare. Despite our best efforts to schedule and contain a life, a controlled explosion is still an explosion. It still makes a real mess. We may sift through the detritus to find pieces of the whole, but it will never all fit together. Mom catalogued our days with precision, and I absorbed and adopted the habit without much thought. Like my mother, I went to my own notebooks; there, I noticed pieces and a pattern. And I suppose I found my reassurance: once I acknowledged that equinox/ solstice alignment, the knocking stopped.

Maybe her journals and mine help me see what is really there, especially if, like the sun on the solstices, I will just occasionally stand still. They help me with my noticing, a writer’s job. They help me get the memories right. They provide evidence: I have handled difficult things in the past, and I can handle them again moving forward. Those nighttime knocks were perhaps a reminder to pay attention. To the natural world. To the seasons. To the time passing. To our inner landscape. To our words. And to treat it all with the reverent, quiet beauty it deserves.

Those are all nice writer things to say.

Reassurances of a sort. But months later, the cigar box of photos, the notebooks, lay open still, like wounds, on the studio side table. I faced the reminders of a life lived, but I don’t know what to do with these remainders. With the grieving. When it knocks three times and whispers low, do I box it all up and put it back in the garage? Do I digitize it? Do I burn it, ceremonially?

Can we cremate grief?

The embers glow slow and persistent on this pyre. I’ll keep paying attention.

——————————————————

——————————————————

Erin Hill is a writer, artist, and educator residing in Yellow Springs, Ohio. Her work has appeared in The Sun, The Under Review, Words & Sports Quarterly, Oh Reader, and The Belladonna Comedy. Find her @erinhillstudio

Photographs provided by the author.