The diesel mercedes

by michael james tapscott

Mark’s instructions were to meet him at the Home Depot parking lot on the 11000th block of San Pablo Avenue. He would be parked in the southwest corner. It sounded a bit conspicuous to me, but when I got there and saw the variety of activities, the logic proved sound. Day laborers clogged the entrances and exits, angry cars jockeyed for parking spots, and a rough and ready Christmas tree farm had been erected right in the smack-dab middle of the commotion. I spotted him where he said he would be, parked in the one calm corner of the lot. The nose of his car was facing a chain-link fence that had plastic shopping bags blown up against it. The car was running and spewing blue smoke into the gray day.

I know nothing about cars, but I know enough that I can tell you that Mark drove a Mercedes and it was not a new one. From the 70s or 80s I supposed. It was piss yellow and labeled “turbodiesel” on the lip of the trunk. On the opposite side of the iconic corporate logo was a bumper sticker that read, “Keep Honking! I’m Listening to Alice Coltranes 1971 Meteoric Sensation ‘Universal Consciousness.”

“Right on,” I thought.

I have some life experience with a diesel Mercedes. When I was twelve, my best friend, Michael Roby, and I decided to chop down a young tree in the public park that was between our homes. There was no prompt or reasoning behind our fury at this dinky oak other than our shared lust for destruction. After going at it with a small hatchet for twenty or thirty minutes, we got bored and lit cherry bombs. This being a small suburban hamlet in the Midwest with little crime and a well-funded police force, the park was soon surrounded.

The reflexive instinct in the mind of the juvenile delinquent or the hardened criminal when seeing red and blue flashing lights is to run. And so we did, though we did not get far. We were trapped in a fishbowl. The park was built in a hollow as a way to manage stormwater and reduce the risk of a derecho flooding the town. Perched on the bluff in every direction, we saw a looming figure in navy blue. Michael stopped first. He dropped the paper lunch bag filled with cherry bombs and froze with his hands up. Seeing he was no longer beside me, I stopped too, but I did not assume the standard position. Instead, I dropped the hatchet, hung my head, and cried. Later, Michael would lack the decency to not mention it.

We were detained on a park bench while someone in central dispatch phoned our moms and dads. The only parent who could be contacted was Michael’s father, who agreed to leave his storefront law office to come retrieve us. Mr. Roby was mostly absent from our day-to-day lives. In the rare moments he was around, he was a stern presence who would brood in his study with a glass of scotch or ice down the dinner table with his silence. He was much taller than all of the other dads in the neighborhood and was devoid of their awkward, beer-drinking chumminess. My own father seemed as cowed and frightened by him as we were.

Mr. Roby smoothed things over in some mysterious way. The police had been threatening us with fines and community service, but all potential punishment vanished into the ether. I was aware he had some pull with the village trustees, but I did not hear what was said. Mr. Roby shook hands with one of the officers, looked in our direction, and beckoned us with a wordless, crooked finger. He guided us into the back seat of his blue diesel Mercedes and drove us home in silence. The car smelled like gasoline and burnt leather. It was the only time I ever rode in it. The incident was never brought up again, and a week later a tree Band-Aid covered the damage we had done. The last time I saw our helpless victim, and it’s been over twenty years now since I laid eyes on the tree or the town, it was thriving. Mr. Roby is long since dead, and Michael has gone down a blue highway too painful to mention.

I shook off the distant past and approached Mark’s vehicle. I found him behind the wheel wearing sunglasses and a sphinxlike expression. He was one of the fully liberated. So in the throes of creativity that he was unable to consider anyone else’s boundaries or feelings.

“Long time, no see,” he said.

“I was taking a break.”

“For what it’s worth, I never thought you had a problem.”

His tiny dog lay sleeping on the backseat which was covered with a Pendleton throw that was coated with the creature’s blue-black hair.

“Is this a new car?” I asked.

“Yeah, I had it converted,” Mark said. “It runs on vegetable oil.”

“I thought I smelled wontons.”

“Funny,” he said, though he did not laugh.

“That’s cool though. Very eco-friendly of you.”

“It’s a pain in the ass.”

As we concluded our clandestine business, I noticed a booster seat in the back and thought to ask about it. Given the circumstances of our relationship, I thought it was best to not swap parenting stories. The less detail we could picture each other’s lives with the better.

“Well, all right then,” I said.

“Yep, see you next time.”

“Right.”

I got back into my vehicle, which has its own stories that I’d rather not tell at the moment, and hung my head in shame.

——————————————————

——————————————————

Michael James Tapscott is a San Francisco Bay Area-based writer, musician, and songwriter. Since 2004 he has been recording and performing under various names. His works of fiction, journalism, and criticism have been previously published in Dusted Magazine, Freedom Fiction, and Nuvo. For one brief, beautiful moment, he was the publisher and editor of the magazine Revolution Blues.

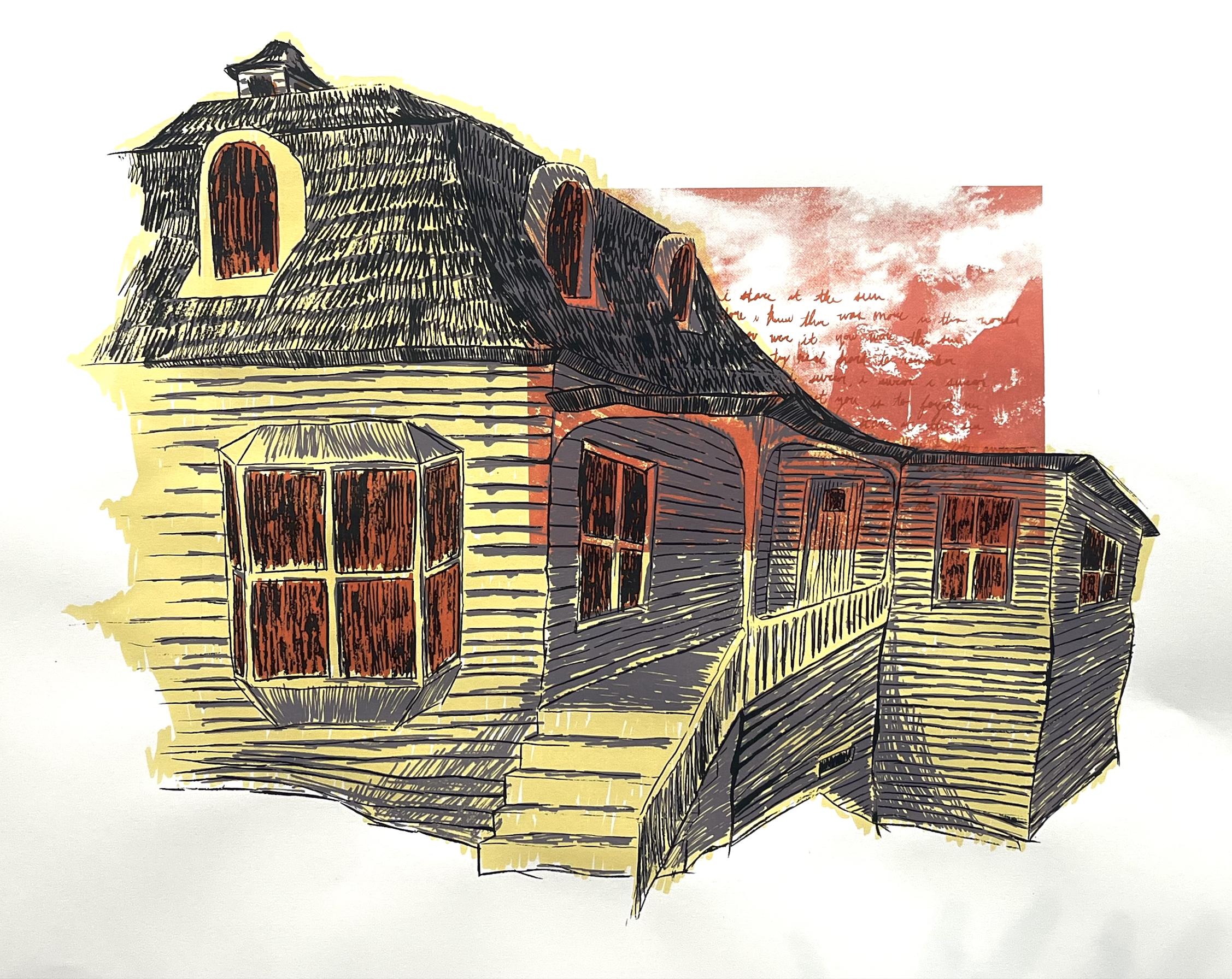

ART BY:

Hallie Krause

The House That I Wanted to Build With You

four layer screenprint, 22”x30”

2024