Forgetting Hong Kong

By Wendy Gan

“Of course, I am scared, but we are more scared of not seeing the faces of our friends tomorrow.” She’s young; you can tell from her sweet, thin voice, and you can hear the emotion that is making her voice tremble. She is one of the protestors rushing back into the Legislative Council chamber to drag out the few who have decided to stay there to await the police and certain arrest. The strategy is that either everyone stays, or everyone leaves together. No one is to be left behind. The reporter to whom she utters this line with such unaffected sincerity is live streaming the chaos of a key event in Hong Kong’s Anti-Extradition Law protests in 2019. Frustrated by the obduracy of the authorities even after two record-shattering demonstrations against the proposed law, a group of protestors breaks into the Legislative Council to express their unhappiness and to make their demands heard. But befitting a leaderless protest movement, there is confusion and indecision as to what to do next. Breaking in is a symbolic act, but once achieved, what then? There is nobody to dialogue with as Hong Kong’s leaders refuse to negotiate and there is a looming threat of the police coming to round up those who have broken in. To be arrested would mean a charge of rioting and a potential jail term of ten years. There are heated debates; there are grand gestures—someone unmasks himself to make a speech; there is anguish. Some leave, some stay, but at the last minute, a group rushes in and hauls everyone out. There will be no martyrs tonight; the movement cannot bear to lose sight of their friends.

I had forgotten that all this had happened. Watching Revolution of Our Times, Kiwi Chow’s documentary on the 2019 Hong Kong protests, brings it all back and I find myself starting to choke back the tears. I was never an active participant in the protests, but I obsessively watched everything unfold via live tweets from journalists on the ground. I am not from Hong Kong, but Hong Kong had been home for more than 20 years and I wanted it to stay proud and free. I remembered hearing the young woman’s words via reports from Twitter. They were moving then; they are still moving now. How did I forget her?

Scenes from the film continually bring back the memories. The middle-aged lady who harangued and pleaded with the riot police till they, tiring of her tirade, pepper-sprayed her point blank. The old man who was part of the Protect the Children squad and who repeatedly threw himself between the riot police and the protestors to buy the protestors time to escape or to embarrass the police into behaving more civilly. The young volunteer medical aide who plaintively begged the police to let him enter Prince Edward MTR station because he had heard that there were people injured inside the locked-down station. I remember reading Tweets about them, playing and re-playing clips of their pleas and cries on Twitter and feeling shattered by their own shattered emotions. There is such raw, life-or-death anguish in their utterances, such incredible passion that, even watching from afar, you can’t help feeling on the edge of despair yourself.

A former colleague of mine had a theory about Hong Kong people. They were brusque on the outside, seemingly worldly-wise, and cynical, but really, deep down they were a bunch of the softest teddy bears. The protests were proof of this: a tough hide betrayed by a righteous indignation and hurt that can only come from those pure in spirit. You can see and hear hearts breaking in the film and that can only happen if hearts are still intact.

How did I forget all of this?

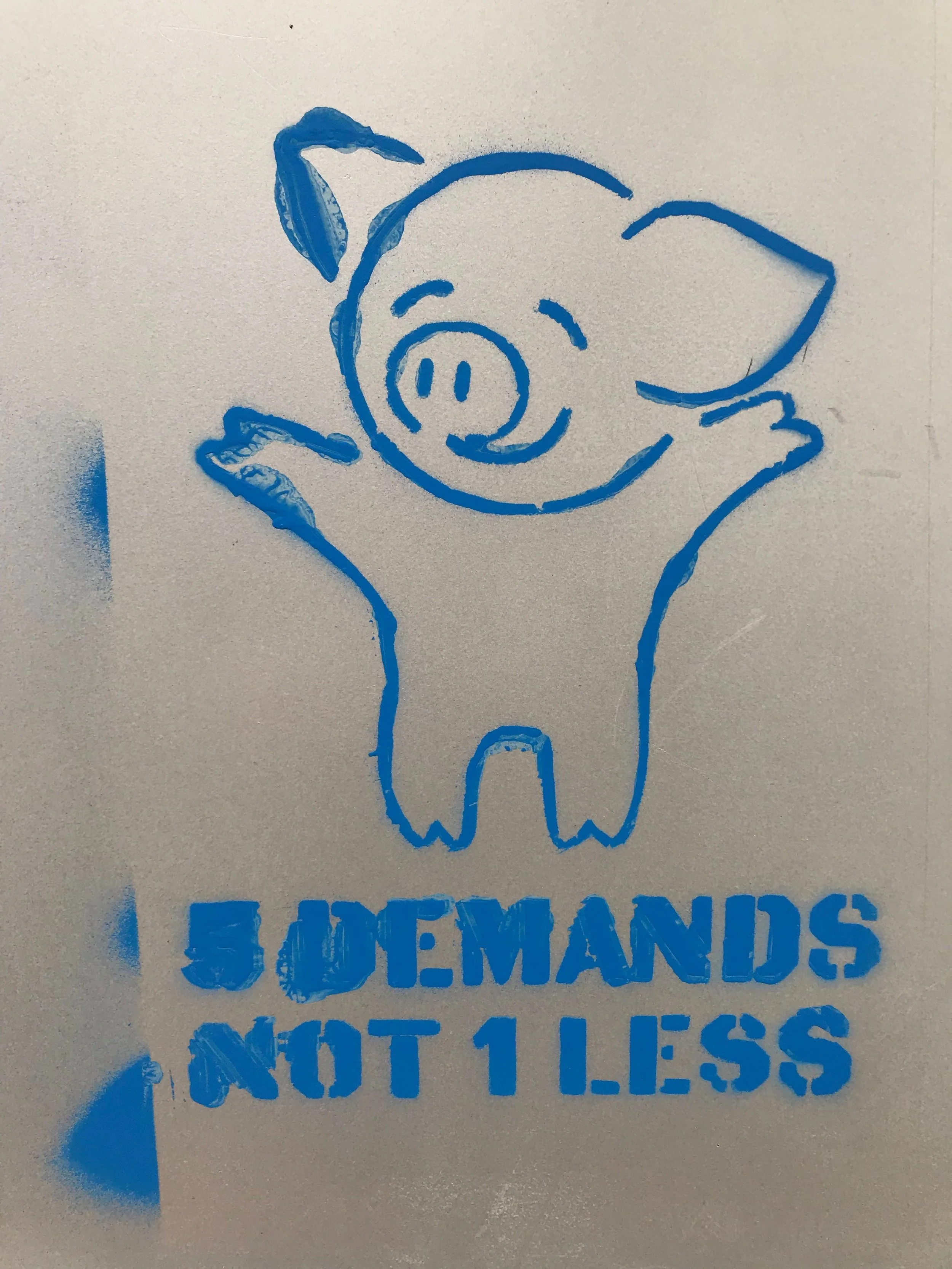

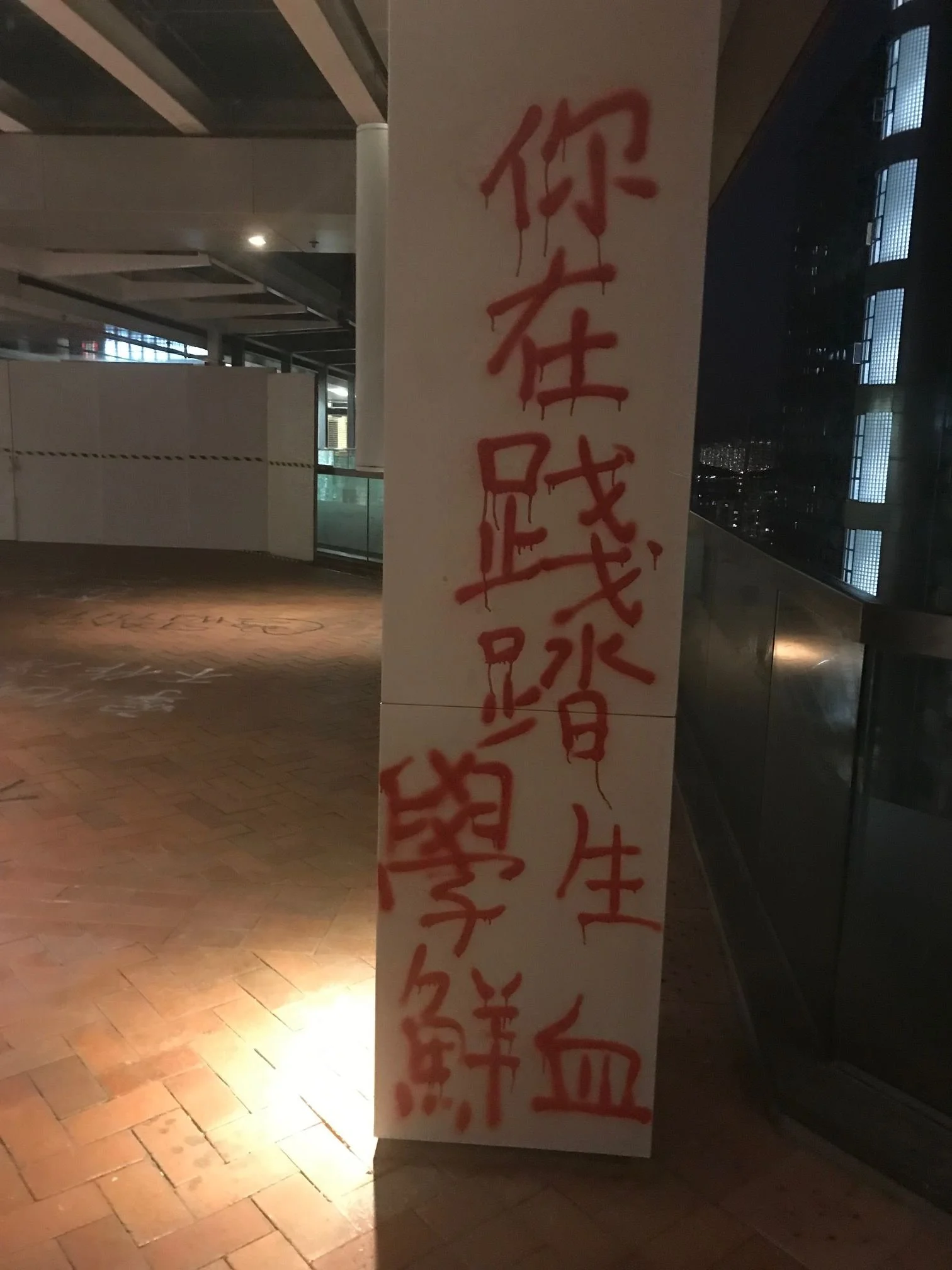

There was a time when it seemed as if it would be impossible to forget the protests. Protest graffiti was everywhere, like black blood seeping out of the city, staining its most prized institutions. It was urgent, dripping with desperation, full of emotion. Each new protest, each new horrific event that either sent shudders down one’s back or else maddened one, made the city bleed black:

—Hong Kong, add oil

—Liberate Hong Kong; Revolution of Our Times

—5 Demands, Not 1 Less

—There are no violent rioters, only a violent government

—When one person breaks the law, it is a question for the courts. When two million break the law, it is a question for the government

—There will be no winners in this revolution, but please be a witness to it

—You are stepping on the blood of students

—If we burn, you burn with us

—Vengeance

But perhaps I already had an inkling then that soon much would be forgotten. Why else did I set out to photograph and record the graffiti? I knew they would eventually be scrubbed clean, wiped away from the walls and eventually from our memories. I even photographed the blotchy efforts to erase the graffiti: the patches of new paint that gave away the fact that protest graffiti once lay scrawled there; the walls scarred with paper scraps where the more stubbornly glued patches of protest posters defied removal; the shadowy, grey shapes left behind by cleaners who had failed to restore the walls to their former pristine condition. I documented the graffiti and its erasure because I wanted to remember it all and because I half-sensed that I would have to forget it all.

Forgetting is part of surviving. You cannot live at that pitch of emotion that the protests brought out in many of us. At some point, you begin to crave the end of the spiraling shocks that each day of the protests deals to one’s nervous system. To encounter a blank wall with no protest graffiti becomes a relief. You want to retreat to the past or else escape to some other place void of the social and political problems that plague Hong Kong. You take a social media break; you compartmentalize; you focus on your job; you deliberately avoid talking politics with your friends; you plan your weekends dodging all protest hotspots; you shrink your horizons so as to hurt less. You put yourself in a straitjacket to function more or less normally, and then realize, with some alarm, that this will soon be your way of life. You still will snap stray pieces of protest graffiti but only surreptitiously with your phone, where it will soon be safely buried in your camera roll by the many more pictures of Instagram-worthy dishes and street cats. As if life was only about food porn and cute cats.

In an authoritarian regime—one that Hong Kong was quickly becoming—forgetting is not just about attempting to regain emotional equilibrium but also political strategy. The arrival of the National Security Law (meant to prevent sedition and secession) in 2020 has elevated forgetting to a completely new level: Tiananmen? What was that? Protests, what protests? Dissent, what dissent? At first, you merely want to forget to stop your heart from breaking further, but soon you are forced to forget more than you bargained for. Then life becomes only about food porn and cute cats.

In 2021, I left Hong Kong for good. There were kinds of forgetting that I felt I needed and couldn’t get while still in Hong Kong, and kinds of forgetting I resisted. The conundrum was that I needed life to be humdrum and ordinary to rest overwrought nerves, but to lead a life of a “Hong Kong pig,” as protestors called their apolitical, pragmatic, bread-and-butter-focused compatriots, was not quite acceptable to me either. Hong Kong was in crisis; its internal structures of judicial independence and basic freedoms were being altered wholesale, even though its exterior had not changed at all. To simply live as if all was well, felt as if I were complicit with a government that was busy saying, “There is nothing happening; there is nothing to see here.” Leaving would be my vote of no-confidence, my refusal to accept the lies.

You leave to forget, and the irony is that leaving is the only way to recover what you have both chosen to and been forced to forget. It is because I am no longer in Hong Kong that I can watch Kiwi Chow’s documentary on the 2019 protests. It’s been banned in Hong Kong because the National Security Law deems it subversive: it tells a version of history that does not accord with what the authorities want. The protestors are braves, not ‘rioters’, self-organized and savvy locals, not dupes funded by foreign governments. Even its title, Revolution of Our Times, taken from a popular protest slogan, has become criminalized. This is a film whose name cannot be spoken any longer in Hong Kong and whose existence has become an important act of resistance. Now that I have moved away, the time to forget is past; I need to remember instead.

* * * * *

We are walking in the middle of a highway. There are no cars in sight and the heat from the tarmac is palpable. Harcourt Road in the heart of Admiralty has been occupied by protestors and the city has come to a standstill. This is unprecedented. There are groups resting in whatever shade they can find. Volunteers are handing out water, snacks, and cold packs meant for bringing down fevers to those who might be overheating. Others are collecting trash from protestors, keeping things neat and tidy in what will become known as the politest and most civic-minded protest ever. The friend I am with says that this kind of logistical forethought is typical in Hong Kong activist organizations.

As I stand at the crest of the highway, looking down onto a mass gathering chanting slogans with a thundering ferocity against then Chief Executive of Hong Kong C.Y. Leung, I can’t help but be shaken, almost intimidated by the fierce will of the people. It feels spine chillingly momentous. Yet in a few months, the Umbrella Movement would turn into a stalemate and peter out. Looking back, I’m not sure what lessons to draw from it all. The Hong Kong authorities however, seem to have learnt from 2014 that the answer is more tear gas and more force.

* * * * *

My friend tells me the first record-breaking demonstration was unbelievable. I had been out of the country and watched it unfold over social media in amazement. There were so many people that she couldn’t even get to Victoria Park, the designated start of the march. She just joined the protest where she could. The heat was extreme and when she felt she could no longer bear it, she broke off to find her way home. She was exhausted and drenched in sweat. She was hoping to take a bus. There were buses, but no way for the buses to travel on the roads. There were at least a million protestors. It would take hours before the roads would be clear for traffic. She had to walk home. She was annoyed, but then immediately felt bad that she was annoyed.

* * * * *

I take myself out to a park for some air after following the protests on Twitter for an entire afternoon. The protests today have been marked by running battles with the police in the central parts of Hong Kong Island. The protestors gather, are dispersed by the liberal use of tear gas, then re-gather in a new location. There are a few jarring incidents of violent arrest recorded by journalists.

The park I am in is busy. There are two half-court basketball games in action. Walkers and joggers are doing their laps and children are shrieking in excitement as they frolic on the playground. About 20 minutes away from here, the police are letting off a fog of tear gas and smashing heads to the ground. The disjuncture never fails to disorient me. Both of these worlds are Hong Kong, and yet they seem so completely separate. Seated on a bench, watching the children chase one another on their little scooters, I ask myself which should take precedence. My nose and eyes start to itch a little. It’s either my sinuses acting up or the wind blowing traces of tear gas to my quiet neighborhood.

* * * * *

It is post-National Security Law Hong Kong, and I can’t believe I am seeing this. There are yellow posters on the exterior wall of this cha chaan teng, clearly indicating that it is a business that supports the protest movement. The most contentious slogans are not on display, but there is a large one that reads “I fucking love Hong Kong.” When “Liberate Hong Kong; Revolution of Our Times” became too subversive to utter, “I fucking love Hong Kong” soon replaced it. The expletive is a particularly Hong Kong touch (Hong Kong protest culture loves profanities), and it also acts as a marker to distinguish the speaker from those who, in their claim to love Hong Kong, have bent the knee to China. It mouths what China-approved ‘patriots’ say with a critical new inflection, but it also expresses a sentiment seemingly safe enough to pass muster in the new Hong Kong. Still, the sight of the bold, expletive-ridden sign on the front of an eatery that faces a busy main road shocks me. The owners have balls. It’s a Hong Kong trait I admire.

* * * * *

I meet with a former student before I leave. She has seen friends and colleagues arrested and is bracing for her own potential incarceration. She tells me she has given her cat to her grandmother because “If the police come for me, she might run out terrified and never be seen again.” She drinks more than she eats. Sleeping is hard for her. I feel like a fool showing her acupressure points that help with insomnia, but there is little else I can offer her. She’s staying in Hong Kong because this is her home, and she wants to keep watch over it even as it crumbles. It’s a decision I respect.

She gives me a book she wrote a few years ago as a parting gift. I press her to keep writing, “Write the story of what it is like from within. It’s the only way out of the darkness.”

* * * * *

There is a breathtaking moment in Kiwi Chow’s film when a drone hovers over a mass of protestors dispersing through the dense network of city streets. Most of the action-oriented sequences of the film are shot at close hand, shoulder-to-shoulder with the group of protestors the documentary is shadowing. This gives viewers a sense of the hurly-burly physicality of the protests: the pushing and shoving that occurs at the frontlines with the police; the rapid, breathless sprints to escape arrest; the adrenalin rush and confusion. Often, shot composition is left at the wayside. You struggle to make sense of the overlapping voices and the messiness of feet, bodies, and hands. This sweeping and swooping drone shot is different. It’s beautiful; it’s transcendent. The protestors are a living, fluid body. Like a drop of spilt water, they shimmy, split, and eventually dissolve into the embrace of the city.

————————————————————————

Formerly based in Hong Kong, Wendy Gan returned to her native Singapore in 2021, where she writes about the cities and natural environments that haunt her. Her writing has been featured in Longreads, Guernica, The Willowherb Review, and Superstition Review.

Featured photos were provided by the author:

5 demands not 1 less by FLB

you are stepping on the blood of students by Wendy Gan

painted over graffiti by Wendy Gan